I often go to the woods, for a respite from the travails of work and life, for adventure, to look for birds or wildflowers, to enjoy the changing colors of fall, to recreate, and sometimes to forage wild food. Most often I head to the small stand of red oaks, maples, and hackberries that cover the oxbow on the Shiawassee River near my house. For a longer escape, I head to the Northwoods of the Great Lakes. Last year, I visited a historic beech forest in Switzerland.

“When I would recreate myself, I seek the darkest wood, the thickest and most interminable and, to the citizen, most dismal swamp. I enter a swamp as a sacred place, a sanctum sanctorum. There is the strength, the marrow, of Nature. – Henry David Thoreau

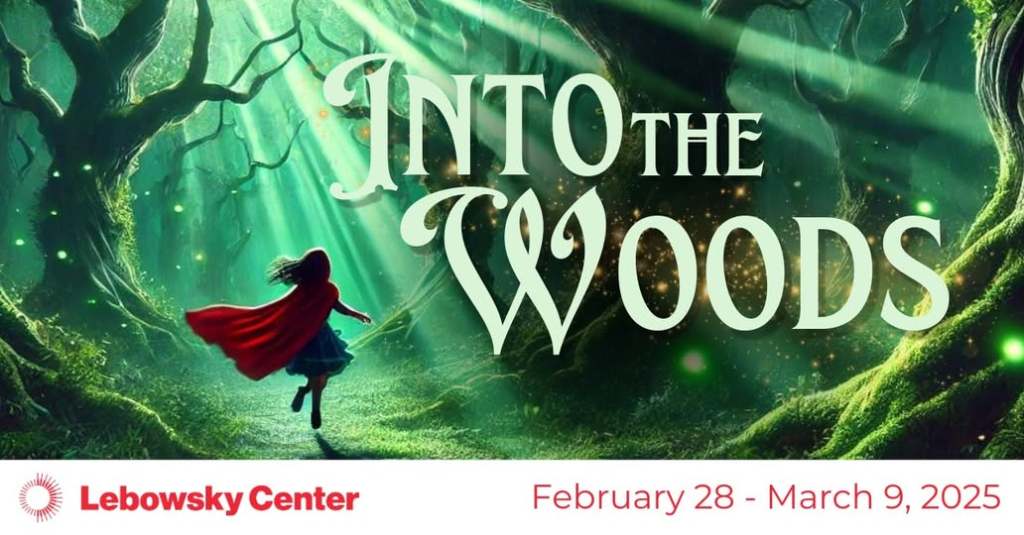

Just recently, I made a metaphorical journey into the woods, and like many a trip previously made to a living forest, the experience forced some introspection, renewed a modicum of joy, and strengthened my resolve. At the Lebowsky Performing Arts Center in my hometown, I saw a production of Stephen Sondheim’s musical “Into the Woods.” My spouse, Anna, played a small role.

“Into the Woods” premiered on Broadway in the fall of 1987, ran for two years, and then became a staple of professional and amateur theater. It was revived twice, in 2002 and 2022, for successful Broadway runs. A significantly edited version of the play was made into a movie in 2014. The year before, the Owosso Community Players put on the musical in a small theater as they worked to rebuild the Lebowsky from a devastating fire. This, and the most recent production, were directed by the immensely talented Garrett Bradley

The musical play in two acts tells about two trips into the wilds of a forest. The characters are mostly familiar to us from the fairy tales of our youth: Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, Jack of beanstalk fame, two generic princes, some mothers, and a witch. But they are not Disney characters, and some audience members struggle with the modified story lines and odd behaviors that present these characters as Jungian archetypes first written down by the brothers Grimm two hundred years ago.

The woods, according to Sondheim, are “the all-purpose symbol of the unconscious, the womb, the past, the dark place where we face our trials and emerge wiser or destroyed.” But the woods are also the solution to the problems facing the characters in the play. They are an escape and in them we feel unbounded. Like the Forest of Arden in Shakespeare’s “As You Like It,” the woods offer its characters freedom from their formal titles, class standing, and even gender identification.

We bring our true selves into the woods, and this is true for the characters in the play. We see the foibles and the integrity of all the characters. One of the adult pleasures of the play is to see the storybook cartoons of our youth transformed into real people with emotions and motivations for good and ill.

In the first act, we see everyone enter into the woods on various adventures. The leads are the Baker and his wife, who seem familiar but are not from Disney or the Grimms. They are on a quest to achieve perhaps that most common and profound of goals: to have a child. We all have a purpose in life (or perhaps purposes?), whether we name it or not, and the first half of the play is about the characters discerning and then seeking their “wish.” And they do get their wish, by effort, some beneficial alliances, and luck (or is there divine intervention from the “old man”?).

The most frustrating part of this musical, like a Shakespeare play, is to catch all the words, which come fast and clever but contain significance. At the end of the first act, the troupe recaps their successful venture into the woods with the advice that

You mustn't stop,

You mustn't swerve,

You mustn't ponder,

You have to act!

When you know your wish,

If you want your wish,

You can have your wish,

No, to get your wish

You go into the woods,

Where nothing's clear,

Where witches, ghosts

And wolves appear.

Into the wood

And through the fear,

James Lapine, who wrote most of the dialogue and collaborated on the lyrics, commented that ”the first act is the fairy tale. The second act is . . really about growing up and real life and understanding the differences between reality and fantasy.” In the second act everyone’s “happy after” and seeming stability are shattered by the appearance of a malevolent force. The characters must return to the forest to either confront, mitigate, or escape the new danger that is beyond anyone’s individual ability to overcome.

What is evil? And what do we do in the face of an inexplicable power that threatens are very existence? I asked myself this question after 9/11, although “Into the Woods” came out before that calamitous event. Given its genesis in the 1980s, some have interpreted the play to be about AIDS, which ravaged the theater community. Life seems to require bad events, and darkness descends too often in too many lives for too many reasons.

I think the dark parts of “Into the Woods” express the reality that unfortunate things happen to all of us. Much of the second act asks the question whether human behavior inherently causes and/or contributes to the negative outcomes of nature. While the characters in the play quickly discern that the destruction of their garden, house, and castle are the result of a lady giant, the underlying reason for the giant’s presence is not easily understood or accepted.

Climate change came to mind the second night I saw the play. The evils of climate change—storms, disease, extinctions—may appear to be a force of nature, but are really a result of the human over-use of fossil fuels that have released record levels of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Like the characters in the play, we all (e.g. humanity) bear at least some of the responsibility for the looming catastrophe.

We don’t want to know about big, scary problems, and do not always take kindly to scientists who attempt to explain the situation to us. In the play, (spoiler alert) the cast turns on the narrator who is telling the story and attacks him for being an outsider. “You need an objective observer to pass the story along” he pleads, but the witch gives him over to the giant in an unsuccessful attempt to appease her and the narrator is killed.

I think this describes the now too common situation when unpredictable dark forces dominate a society. Without objective data, misinformation thrives and suspicion abounds. Then, as in the play, there is a lot of assigning of blame for the problems that beset us (see the song “It’s Your Fault”). Others, who have more ability to effect change (the Prince and his steward) often dither and fail to act. Those with money or privilege (Cinderella’s relatives) simply retreat in an vain attempt to escape the problem. It’s only the characters living in poverty (Jack and his mother) who are willing to confront the giant.

Without a narrator to tell the story, the play descends into “a world of chaos.” It’s how I feel these days. A year ago, I was excited about the prospects for meaningful climate action in our country and community. Now, we seem to have even stopped talking about the “giant” of climate change stomping about our planet. Even those who attempt to narrate the story are ignored, dismissed, or attacked.

“Disoriented” is the word that comes to me. It derives from the days of early map-making when one would orient a chart by turning the top to the east, or the orient in the language of the day. To be disoriented is to be uncertain and without a sense of direction. On the floor of the raked stage in the Lebowsky there is a compass rose. Where do we turn for guidance when we are lost?

Human relationships, the cords that tie us to one another, run through “Into the Woods.” Relationships are often strained and fray in this story, and there are several scenes of tug-of-war between characters. The central relationship may be the marriage between the baker and his wife, but mother-daughter and father-son relationships drive the plot as well. And we laugh at the relationship between the brother princes.

Sometimes, as in real life, relationships problems undermine our capacity to act, but just as often the help of another gets us through a difficult place. The debilitating loss of a relationship, by death or distrust, also occurs in the “Woods.” However, new relationships are formed, particularly in the second act. One of the concluding and powerful songs in the show is “No One is Alone“ which might be the moral of this story.

The key message of the second act, perhaps of the play, is that only by coming together with others can we defeat wolves, giants, and our own shortcomings to escape the darkness. The finale, a reprise of the song “Into the Woods,” starts with a change in lyrics from the first act, which emphasized discrete deeds and individual effort. Rather, now the cast is encouraged to go slow and cooperate:

You can't just act, You have to listen. you can't just act, You have to think.

The song warns us again that there are dangers of giants, wolves, spells, and beans with unintended consequences in the woods. However:

The way is dark,

The light is dim,

But now there's you, me, her, and him.

Here, at the end, we are reminded that despite our reluctance, insecurities, and failings we need to venture into the woods “every now and then . . we don’t know when” with others to confront evil and restore us to our purposes.

Be ready for the journey.

Into the woods, but not too fast

or what you wish, you lose at last.

Into the woods, but mind the past.

Into the woods, but mind the future.

What of the future? That is the question the play didn’t answer well for me. In our current unsettled times, I had to work to find some comfort and inspiration. At the start of World War I, the author Virginia Woolf wrote “the future is dark, which is on the whole the best thing the future can be.” Too often these days, the darkness of the future depresses me. I think though that Sondheim would agree with Woolf: we are never guaranteed a secure future, something that “Into the Woods” burdens its characters with.

Nonetheless, we do have the power to negotiate the darkness and define at least the direction of our own future. “Hard to see the light now. Just don’t let it go.” Is a line from the song “No One is Alone”. “Things will come out right now. We can make it so,” but only if we work together to defeat specific wolves and giants, and not be overwhelmed by the darkness.

Nature, woods, and wilderness come to my mind often, and they did again watching this play twice over the last weekend. While I generally relish an outdoors adventure, wild places separated from civilization are inherently dangerous. I believe we have more to gain than to fear from wilderness, but I rarely venture far, or long, into the woods on my own. In 2006, I spent six weeks hiking solo across Michigan’s Upper Peninsula from the Mackinac Bridge to the tip of the Keweenaw Peninsula, but only with serious preparation, a careful plan, and a support system.

In literature and the arts, nature can play a dual role, sometimes being a dangerous locale of feral animals, outlaws, and other representations of evil. But the woods can also be a garden, even a paradise, of earthly delights of flowers, fruits, and other sources of re-generation and growth. The Bible of course starts its story in a garden in the old testament story of Genesis. The penultimate moment in the life of Jesus as told in the new testament takes place in a garden, Gethsemane, where he is betrayed by one of his followers and captured by soldiers of the empire.

“We give our forests meaning with the metaphors we choose to represent them and the stories we learn to tell about them,” says University of Michigan English Professor John Knott who wrote “Imaging the Forest: Narratives of Michigan and the Upper Midwest” which reviews the literary depictions of the Northwoods from Longfellow’s “Song of Hiawatha” to Jim Harrison’s “True North”

“Into the Woods” is a collection and rewriting of stories and asks the audience to consider their own story. With so many archetypal characters in the story we have several roles to identify with. We all have the power to tell our own story, but this is not a fairy tale. “Careful the tale you tell, that is the spell,” reminds us that of the profound impact of our choice of story.

Where to find hope? Is a question I wrestle with daily in our current times when darkness seems inexplicable, overwhelming, and very scary. The play gives us two sources of hope: children, and nature. The original quest into the woods is for the Baker and his wife to overcome a curse of infertility. And one of the constants, and perhaps the moral of the story, is the line “children will listen” delivered along with commentary about the parent-child relationship. The play ends with the Baker fully embracing his responsibility as a father with the support of other characters.

The play gives us several moral dilemmas to choose from, and while the message of “You Are Not Alone” is clear, it does contain the lyric “you decide what’s right, you decide what’s good.” We all have agency and responsibility, but we cannot act without awareness of those with whom we are in relationship. And to overcome darkness and existential ennui we need to work with one another, even though the difficulties and obstacles are unclear and immense.

Nature as a source of hope may be less obvious, and is complicated by the fact that the woods is both a natural and supernatural feature in the drama. What I saw in the second viewing was the importance of the birds, highlighted by Director Bradley’s decision to have them show up on stage as puppets with a human counterpart. The birds, one of the things in nature that gives me joy, help Cinderella in the beginning of the play, and at the end she calls on them again to help defeat the lady giant who threatens their safety.

Nature can be both a source of beauty or recreation, and a tool to help us overcome the challenges we face. This truth has become the centerpiece of those, like The Nature Conservancy, that advocate for natural climate solutions. Protecting the Northwoods, preserving swamps and peat bogs, and planting trees all help take carbon out of the atmosphere. It’s not the cure-all to all of climate challenges, but it can be a big part of the solution.

Whatever the difficulties of the complex science of climate change, the economic barriers to implementing new energy technologies, and the political setbacks we endure, we are on an unavoidable quest to improve life on the planet. For me, going to nature inspires me to do the work before us:

Into the woods--you have to grope,

But that's the way you learn to cope.

Into the woods to find there's hope

Of getting through the journey.

These two photos are from the Michigamme Highlands in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, an area of old growth forests, historic logging and regrowth, and one of my favorite places to go into the woods.

Thanks to the Mattesons Photography for the excellent photography of Lebowsky Productions, including Into the Woods.